Badges and Hoods

How White Supremacy Shaped American Policing

Every nation tells stories about its protectors. In America, the police are cast as guardians, the thin blue line between order and chaos. The true origin story is different. The first police in the South were not guardians of public safety. They were slave patrols, charged with hunting human beings and crushing freedom at its roots.

From those patrols grew a system where the badge and the hood often belonged to the same man. The Ku Klux Klan did not rise outside the law. It rose alongside it, shielded by sheriffs and deputies who chose loyalty to white supremacy over loyalty to justice.

This is not a story of a few bad apples. It is a story of design, inheritance, and continuity. To understand why racial violence and police power remain so tightly bound today, you have to trace the lineage back to where it began.

The patrol, the Klan, the badge.

Part I. Origins in White Control

Slave Patrols to Reconstruction

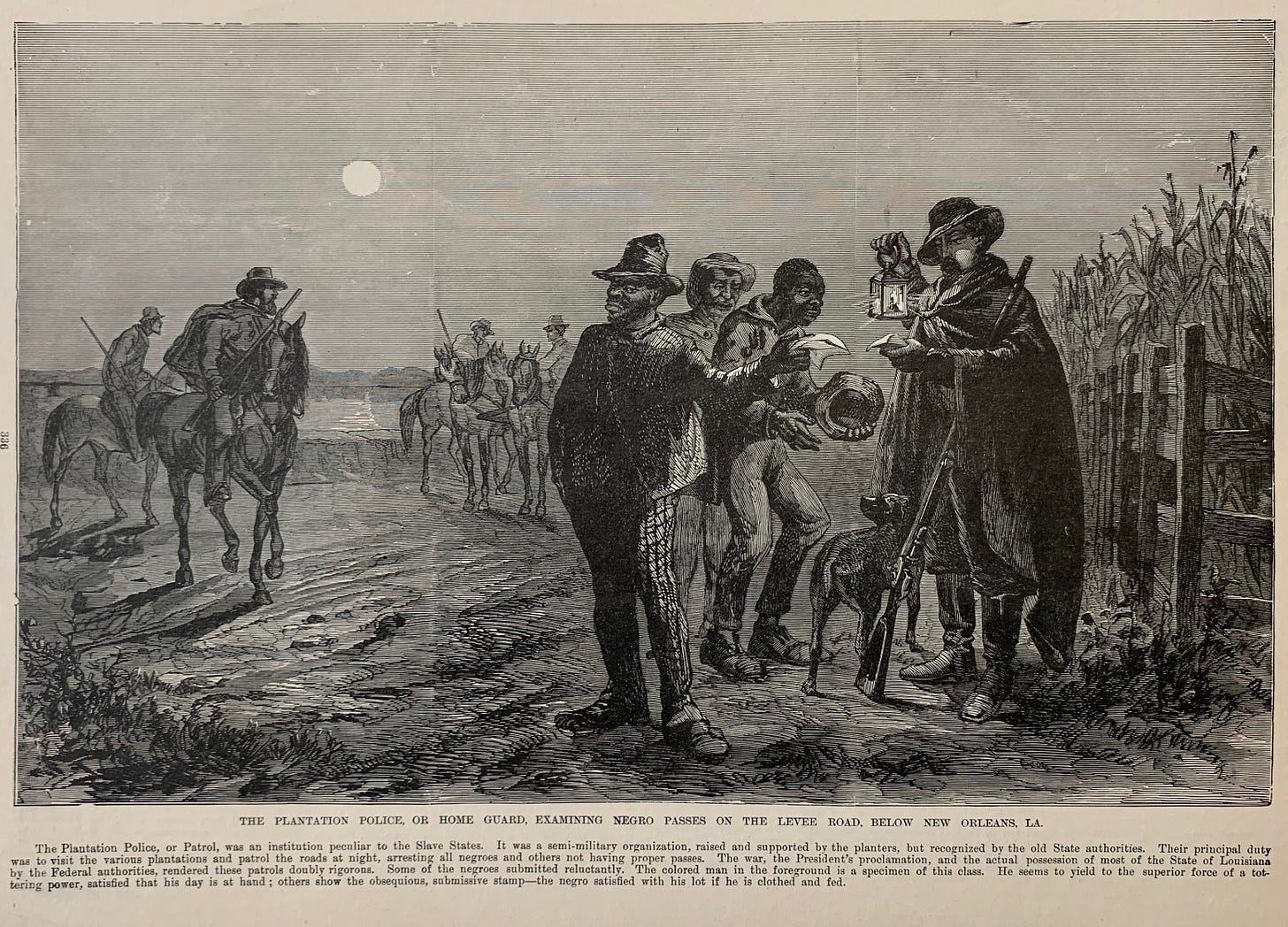

The first police forces in the American South were not built to protect communities. They were built to protect property, human property. Beginning in the early 1700s, colonies such as South Carolina and Virginia wrote slave patrols into law (link). Groups of armed white men roamed roads and plantations to hunt runaways, break up gatherings, and punish anyone who challenged the racial order.

On all slaves found off their owner’s premises, without written permission from some person legally authorized to give such permission, you will inflict not more than fifteen lashes; no slave to be whipped except in presence of the Captain. You will arrest and carry before the Intendant of Police, all free colored men found associating with slaves in the night, or on the Sabbath day, in any kitchen, out-house, or place other than his own premises.

Historian Sally Hadden calls them “the closest thing to police in the antebellum South.” Their mandate was surveillance and subordination. The badge, at its origin, was designed to keep Black people under control.

When slavery ended, the patrols did not disappear. They mutated. Southern legislatures passed the Black Codes (link), laws that made unemployment or vagrancy into crimes. Freedmen could be arrested, fined, and leased back to mines, railroads, and fields. As Douglas Blackmon writes, it was “slavery by another name.” Police stood at the front line of that system, arresting men not for what they had done, but for who they were.

The Rise of the Klan

At the same moment slavery collapsed, the Ku Klux Klan was born. In 1865, former Confederate officers founded it as a secret fraternity. It quickly became a paramilitary force, dedicated to restoring white dominance by terror.

The 15th Amendment (1870) outlawed denying the vote based on race. Reconstruction governments in the South saw Black men voting, holding office, even shaping constitutions. For a brief window, democracy widened. But the Klan rose up as the shadow hand of white supremacy to strip that promise back.

The Klan burned schools, attacked voters, lynched teachers, and drove families from their homes. None of it would have lasted without the complicity of law enforcement. Sheriffs and constables turned their backs, juries refused to convict, and in many towns the same men wore both the badge and the hood.

Congress saw the overlap clearly. In 1871, lawmakers passed the Ku Klux Klan Act, authorizing federal troops to intervene where local lawmen refused. Testimony from that era was blunt: “The sheriff’s badge is often the same man’s hood.” For a moment, the federal government admitted what people already knew. Policing and racial terror were entwined.

Part II. Institutional Overlap

Lawmen in the Hood

By the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan was no longer a shadowy group of night riders. It was a mass movement with millions of members and open parades down Main Street. Judges, sheriffs, and police chiefs were not just bystanders. Many were card-carrying members. In some towns, the same man wore a badge by day and a hood by night.

The pattern endured. In 1981, the leader of a Klan subgroup in Kentucky, the Confederate Officers Patriot Squad, was a county police officer (link) “About half of the group’s members were police officers,” the Brennan Center later reported, and the department “tolerated his membership so long as he did not publicize it.” The line between officer and Klansman was deliberately blurred.

Federal agencies knew this. A 2006 FBI assessment warned of “white supremacist infiltration of law enforcement.” Cases confirmed the fear. (link) “Members of the Ku Klux Klan were found in police departments in Texas in 2001, in Florida in 2014” (link). The hood and the badge still fit the same hand.

Policing Jim Crow

At the same time, law enforcement served as the muscle of Jim Crow.(link) Officers did not just enforce criminal law. They enforced a racial caste system.

Brandon Jett describes the contradiction:

“African Americans were over-policed in the sense that they were arrested for high rates of nonviolent offenses … while simultaneously under-policed in the sense that law enforcement officers typically showed little concern for crimes involving Black victims.”

Vagrancy, loitering, and disorderly conduct charges became tools of social control, feeding Black men into convict leasing camps that profited from their labor.

Margaret Burnham extends the frame: “Enforcement of Jim Crow norms was carried out not only by police, but by bus drivers, librarians, clerks, and ordinary white citizens, who assumed the authority to police Black life.” Jim Crow was a web, with the badge as its core thread.

Continuity

This overlap has never fully ended. A Reuters review found “scandals in over 100 different police departments, in over 40 different states, involving explicit police racism.”

The report concluded:

“The presence of law enforcement officers participating in white supremacist organizations or activity is not a matter of isolated incidents. It is a systemic concern.”

From the 1920s Klan parades to the 1980s Kentucky squads to the 2000s FBI warnings, the story is consistent. Law enforcement and white supremacy did not simply coexist. They reinforced one another, bound together in personnel and purpose.

Part III. Continuity into the Present

Cross-Burning and Badge-Wearing

By the mid-twentieth century, the link between police and the Klan was not rumor. It was visible. Civil rights workers reported officers guarding Klan rallies, passing intelligence to chapters, and sometimes joining the night rides themselves. The Department of Justice logged case after case of local lawmen complicit in racial terror.

On the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965 (link), it was uniformed officers who swung the clubs. The robes had been traded for badges, but the purpose was the same: preserve a racial order under threat.

Even decades later, revelations continued. In Louisiana, Florida, and Texas, officers were exposed as active Klan members. In one case, entire shifts of deputies were implicated. What communities had long said was true. The line between vigilante and officer was paper thin.

The Systemic Legacy

The danger is not just infiltration. It is inheritance. Policing in America was designed to enforce racial hierarchy, and that imprint endures.

Warnings have been steady. A 2006 FBI intelligence assessment flagged “white supremacist infiltration of law enforcement.” In 2020, the Brennan Center catalogued repeated scandals, from officers in extremist groups to departments tolerating racist propaganda. And in 2022, Reuters tallied “scandals in over 100 different police departments, in over 40 different states, involving explicit police racism.”

The legacy is plain. Black neighborhoods remain disproportionately policed, swept up in arrests for minor offenses. Protesters demanding accountability are met with militarized crackdowns. The logic of the slave patrol, surveillance, control, and racial order still shapes the mission.

Closing

The record is clear. The patrol became the police. The hood became the badge. And the system carried forward without ever cutting those roots.

When scandals break today, when officers are exposed in extremist groups or departments tolerate open racism, they are not new infections. They are old scars reopening. The structure was never cleansed. It was repainted and passed down.

To speak honestly about policing in America is to admit this continuity. Slave patrols, Klan alliances, Jim Crow enforcement, modern infiltration, they are chapters of one book, not separate stories. The badge and the hood grew together. Until the root is reckoned with, the tree will keep bearing the same bitter fruit.

ETHER

The record is clear: the patrol became the police, the hood became the badge.

Each generation swore it was different, but the inheritance never changed.Slave patrols wrote the orders. The Klan enforced them.

Sheriffs signed their names on both. Law and terror marched hand in hand,

one in daylight, one at night.This is not infection. It is design.

Not a few men gone astray, but a lineage,

a blood-stained genealogy of power.And the mask remains.

Some nights it is a hood,

some days a badge,

but it is the same face beneath.

Until that root is severed,

the fruit will always be bitter,

the siren always another

chain rattling in the dark.